Guest Post by Danae Peckler, Architectural Historian and Board Member of the National Barn Alliance

Recently listed on Preservation Virginia’s Most Endangered Historic List of 2012, The Meadow Farm, will be auctioned off on May 22nd at 2:00pm EST. Birthplace of the 1973 Triple Crown-winner Secretariat, the 331 acres that remains of The Meadow is situated within Caroline County, Virginia, just east of Interstate 95. Nearly 34 years after the Chenery family sold the farm, it is now threatened by the development pressures that accompany any property near an Interstate exit. But it is perhaps more at risk from those who do not know its rich, yet humble history.

In 2006, The Meadow was determined to be eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (SHPO). Although the main house was no longer standing at that time, it was determined that the historic significance of The Meadow as a notable twentieth-century breeding and training farm of Thoroughbred racehorses was clearly conveyed through the physical components that survived from the Chenerys’ tenure.

Extant historic features at The Meadow include a number of training, yearling, stallion and broodmare barns, as well as the foaling shed where Secretariat was born in 1970. Other historic structures such as machine sheds, hay barns, secondary dwellings, garages, a pump house, and a horse cemetery also remain. But perhaps more telling, and less visible to the “urban” eye, are the various historic landscape features, including the path of the old racetrack, numerous paddocks and pastures, fences lines, farm roads, and field patterns—all of which continue to reflect The Meadow’s equine and historic agricultural use for the past 250 years.

Secretariat’s Foaling Shed has been relocated from the pasture behind the main house to the middle of the old racetrack, where it is preserved as an artifact for State Fair patrons to observe, near the new equine facilities.

The historic buildings, structures, and landscape features at The Meadow comprise the birthplace of a great champion, but these elements also reflect the dedication and hard work of a prudent horseman. The story of Christopher T. Chenery and his Meadow farm was recently published in Secretariat’s Meadow, a book by Chenery’s granddaughter, Kate Tweedy, and Leeanne Ladin. The book tells the tale of how a man from little wealth came to own one of the most celebrated racehorses in history, and how his family’s ties to a farm in Caroline County carried him back to ‘Ole Virginny.’ In addition to establishing the Meadow Stable, Christopher Chenery was instrumental in the creation of the New York Racing Association (NYRA), the non-profit organization that continues to oversee the Belmont, Saratoga and Aqueduct racetracks, and shaped horse racing on the East Coast for much of the twentieth century.

Building on her father’s dedication, Penny Chenery Tweedy enabled the success of Secretariat, but also the 1972 Derby winner, Riva Ridge. Penny’s own contribution to sport of Thoroughbred horseracing in the late-twentieth century cannot be understated. All told, the Chenery family’s hard work has immortalized a little piece of land in Caroline County, and endeared it to the hearts of countless Americans. The physical landscape at The Meadow continues to tell their story, and the story of so many people (and horses!) that helped bring the farm’s history to life, to those of us who look to listen.

But don’t be fooled, The Meadow is not the horse farm we see in today’s movies. This farm was not lavishly built by an oil tycoon and it did not become the corporate headquarters of international investors in the racing industry. Its historic barns and farm buildings are not grandiose in size or architectural detail. The historic fence lines and gateways on the property are not enlarged signposts—there was certainly no need for billboard-like advertising in Chenery’s era—everybody knew where the farm was located and who was working there. And if you didn’t, you just had to ask someone local.

This training barn is one of the few original features remaining on the south side of the farm, and is located in the center of the old racetrack. This barn and the foaling shed are now largely surrounded by pavement and enclosed behind a tall metal fence.

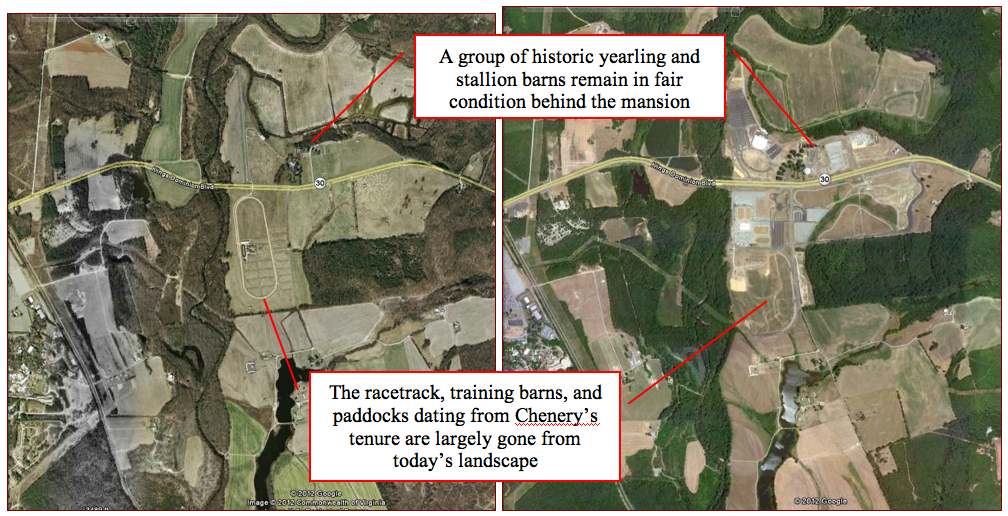

Today, The Meadow continues to be a rare find among celebrated mid-twentieth century horse farms. Despite improvements made by subsequent owners and new construction associated with the State Fair of Virginia (SFVA), the authenticity of this culturally significant historic landscape remains visible, with much of it lying just beneath the surface. Aerial photographs taken in the mid-twentieth century reveal that the air-strip, observation tower, and current mansion were added in the mid-1980s, while the SFVA has added parking lots, event buildings, and new roadways since their occupation in 2009.

Satellite imagery illustrates the farm’s transition to host the SFVA. Pictured at the left is an aerial view of the farm in 2002, and at right, an image taken in 2010 (Google Earth).

Given the farm’s high-level of historic significance, it is hoped that the farm’s new owners will be sensitive to historic fabric that remains of Secretariat’s Meadow farm, and perhaps even restore some of Chenery’s design. No one needs to gussy up the real deal; The Meadow’s visitors would be better served by even a slice of an authentic experience of Virginia’s most well-known horse farm.

If you are interested in learning more about the farm’s auction next week, please visit the website of Motley’s Auction House and click on the 331-acre Virginia State Fairgrounds Complex in Doswell, Virginia (http://www.motleys.com/index.php). The auction will be held “on site” and “on line,” but online bidders must be registered by May 18th at 3:00 pm EST.